Learning Guide

TE MATA RONGOĀ MAARA

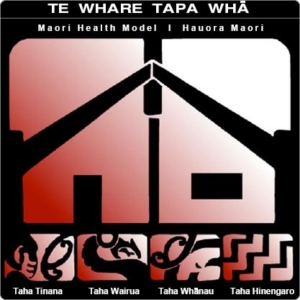

Rongoā Māori is a system of practices and tikanga (principles) that aid in healing and hauora (wellbeing). While the focus of this learning guide is rongoā rākau, where we use plants to and developing a relationship with our natural world, it is important to acknowledge that rongoā Māori is not limited to rākau and includes a range of other practices of which wairua (spirituality) is an integral part. Some examples are the body-work practices of romiromi and mirimiri, as well as the use of taonga puoro (musical instruments), mahi toi (art), karakia and takutaku (types of prayers and incantations).

Rongoā comes from a tradition of living as a part of the natural world, and the accumulation of generations of close observation of every detail (Pa McGowan, 2019). As such, rongoā is very specific to our beautiful homeland of Aotearoa and its particular plants and species. While plant identification skills are critical to learning rongoā rākau (the misuse of a plant could result in serious harm or even death), it is important to understand that rongoā isn’t just about using plant constituents to cure our mamae (ache, pain, injury, wound). To truly learn rongoā Māori you must also develop your understanding of te ao Māori (the Māori way of understanding the world).

This learning guide has been developed by Tyne-Marie Nelson to support people to learn about rongoā Māori – particularly rongoā rākau. It will be particularly helpful for those at the beginning of their journey. Please note, from here on in where the term rongoā is used throughout this guide we are using it in relation to rongoā rākau.

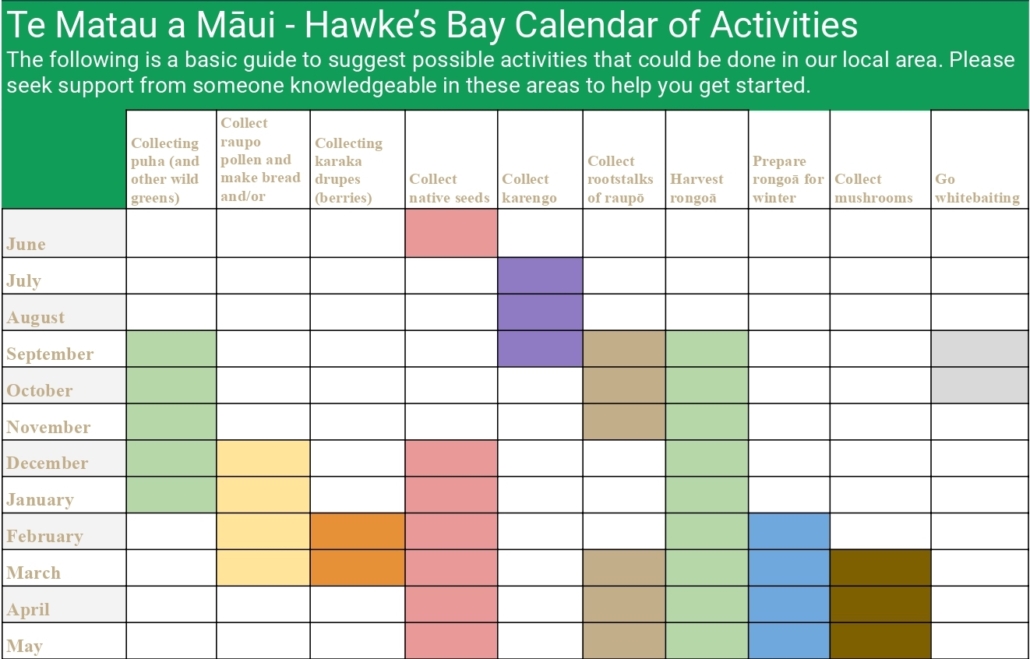

familiar with, which is based on the cycles of the sun and begins with January 1st and ends December 31st. Instead, the maramataka new year begins within the period of June-July, specifically with the first new moon following the appearance of Matariki (Pleiades) or Puanga (Rigel), depending on where you are in the country.

familiar with, which is based on the cycles of the sun and begins with January 1st and ends December 31st. Instead, the maramataka new year begins within the period of June-July, specifically with the first new moon following the appearance of Matariki (Pleiades) or Puanga (Rigel), depending on where you are in the country.

Five times winner of the prestigious international green space award.

Five times winner of the prestigious international green space award.