Learning Guide

NATURE’S RECYCLERS: FUNGI

Chlorophyllum rachodes

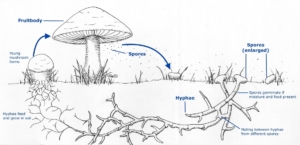

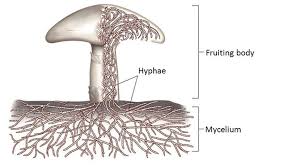

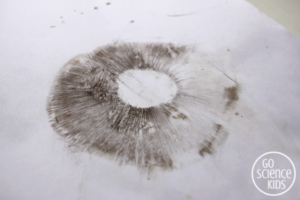

The many fungi in the Park are mostly beneath the soil and out of sight until they push up fruiting bodies in the form of a mushroom or toadstool. They do this when conditions are suitable, most frequently after warm rain. The fruits are tiny spores which may be moved about by wind, rain, and passing feet amongst other mechanisms.

Beneath the surface is the main part of the fungus, a system of roots called a mycelium which you may see as a beautiful fine white ‘tree’ if you turn over a wet piece of wood. Most trees have an intimate relationship with one or more species of fungus at the level of the finest roots. There is a busy and variable exchange going on – the tree transfers energy produced by photosynthesis and the fungus provides soil chemicals to the tree. This process is obviously tricky to study but is slowly becoming better understood.

Fungus is also a decomposer, crucial in the process of breaking down dead organic matter, recycling that waste into nutrients for the plants and soil. They are the recyclers of the natural world. Without them, most dead organic matter wouldn’t decompose (break down), and instead would just build up around us. (Source: Mike Lusk)

Here are a few of the fungi you may see while walking in Te Mata Park (captured in Te Mata Park by Mike Lusk). When observing fungi in the Park, please use only your eyes and do not eat or touch them.

symbiotic relationships with plants or animals.

symbiotic relationships with plants or animals.

Five times winner of the prestigious international green space award.

Five times winner of the prestigious international green space award. Source: Mike Lusk

Source: Mike Lusk